When I first viewed the video of Walter Scott being gunned down by North Charleston South Carolina police officer Michael T. Slager my mind raced up north to Teaneck New Jersey. The horrific scene of Scott being shot in the back multiple times, eight shots fired to be exact, was eerily similar to the killing of 15 year-old Phillip Pannell by white Teaneck police officer Gary Spath in 1990. Scott and Pannell posed no threat to the respective policemen and in the case of young Phillip; he was gunned down with his arms raised in a surrender position.

It hardly seems possible that Phillip Pannell was killed 25 years ago today but the killing of Black men by police has been so epidemic that a death two decades ago can be casually forgotten. Yet, what happened to Phillip is so symbolic of the experiences of Black youth that his death cannot be in vain. An encounter with a police officer suddenly turns into a confrontation and quickly spirals into violence, leaving a young Black man dead. This was no Detroit, Brooklyn or Cleveland. We are talking about the ‘burbs, the tree-lined streets and well-manicured lawns of a New Jersey suburb that prided itself on being a symbol of diversity and boasted of having voluntarily integrated its schools in the 1960s. That reputation did little to stem the anger of Black youth or the pent up resentment of whites in Teaneck that spilled over in an ugly display in the weeks and months following Phillip’s death.

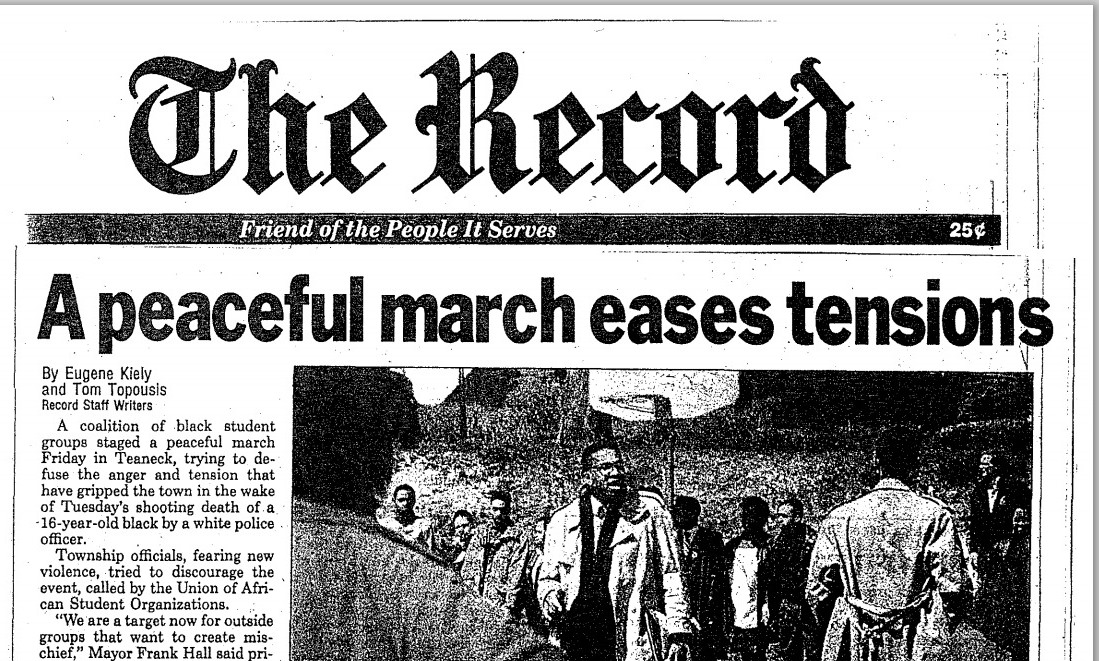

I came to the Pannell incident as a local NAACP leader and became involved after waking up to news reports the morning after he was killed. At the time I was a graduate student at NYU and just weeks from receiving my degree when the news served as a splash of cold water in my face. Hearing that a Black child had been killed by a police officer in a community that neighbored my hometown seemed surreal at the time. It became very real the next evening when the anger of youth erupted at a prayer vigil for Phillip and bands of young people vented their frustration by burning police cars, breaking windows in the municipal complex and in the shopping district. My shock was shared by two good friends, Salaam Ismiall and Charles Webster, as we tried to make sense of it all and worked to channel the anger of Black youth into a focus on advocating for justice for the Pannell family. Phillip was killed on a Tuesday and the prayer vigil was Wednesday, and on Friday – Good Friday – my two friends and I led about 100 college students in a peace walk through Teaneck. On the morning of Easter Sunday I was squirreled away with attorney Ted Wells in the office of my attorney Arthur Martin briefing Wells on the incident and imploring him to represent the NAACP; which he did.

What might bring justice for the Scott family is the existence of eyewitness video that shows the victim was no threat to the officer. After the videotape of the shooting surfaced, the North Charleston police department acted swiftly to charge Officer Slager with murder and remove him from the force. Troubling is the fact that up until the video was revealed the department was defending Slager. Twenty five years ago there was no video evidence of the killing of Phillip Pannell. In Phillip’s case the initial autopsy was botched by the Bergen County coroner and a grand jury refused to indict Officer Spath. However, when a second autopsy was conducted it clearly showed that Phillip was shot in the back and had his arms held up in surrender. Phillip posed absolutely no threat; he was cornered in a backyard with a high fence and had given himself up. During the first autopsy the coroner had failed to put the jacket Phillip was wearing when he was shot on the deceased teen, and when he did and raised Phillip’s arms, all the bullet holes aligned. New Jersey Attorney General Bob Del Tufo, with the support of then Governor Jim Florio and the county prosecutor Jay Fahy, ordered a second grand jury and Spath was indicted. Still, months later an all-white Bergen County jury acquitted the officer. There would be no justice for the Pannells.

The contrast in the public reaction to Scott’s murder, and that of Eric Garner and Michael Brown, to the killing of Phillip Pannell in 1990 is worth noting. There was dissension within the Black community over Phillip’s death as many middle class Blacks in Teaneck were more concerned with protecting status than demanding justice. I know because my encounters with many Blacks in the suburban community, including county NAACP Board members, left me dumbfounded and angry. It was clear that many thought Phillip did not have the appropriate pedigree for them to expend such energies on his behalf. Then there were so-called liberal whites who wanted to trade on some mythic commitment to civil rights to divorce themselves from any responsibility for an environment in which many Black youth clearly felt alienated and under constant harassment. In an April 22 New York Times article on the shooting, Teaneck resident Irwin Moskowitz was quoted as he witnessed a march to protest the shooting. ''We are appalled by the killing, but not as much as we are appalled by this,'' he said. ''This is an example of people who have no knowledge of what has happened in Teaneck for 30 years and who have no real commitment to the concept of integrated living.'' It was clear that for many in Teaneck justice was a secondary consideration to the appearance of integration.

For Black youth, there was a palatable and understandable anger. I had to escort the best friend of Phillip to the dead youth’s funeral because Teaneck police had arrested him on a trumped up charge related to the incident the night of the prayer vigil. It took the county prosecutor to arrange for the young man to be turned over to the neighboring Englewood police, and then to me, so he could pay his final respects to his friend. A grief stricken young man who spoke during the funeral service asked simply, “Who is protecting us from the police?” Those moments in that church remain some of my most heartbreaking, and I feel that way even recalling the passing of my parents.

Making matters worse was the behavior of the local police union, organizing a massive march and rally at the county courthouse for Officer Spath that attracted thousands of police officers from across the country. We also had to confront the local press, the Bergen Record, because it ran a mug shot of Phillip from a prior juvenile offense. I called the owner of the paper, Mack Borg, and to his credit he ordered his editors into a conference room with me and other community leaders I selected to address the inappropriateness of using the mug shot. The paper never used the photo again in its coverage of the incident after that meeting.

My hope is that the family of Walter Scott receives real justice in the form of a conviction of Officer Slager for murder and an appropriate sentence. No family should feel the pain the Pannells felt twenty five years ago, and continue to carry today. My conscience will not allow me to forget the young boy I first met as he laid in an open casket. It is an image that I cannot forget and a hurt that no amount of time can heal. Phillip Pannell is not forgotten and his death serves as a reminder that we can’t take a day off in the struggle for justice and dignity.

Walter Fields is Executive Editor of NorthStarNews.com.