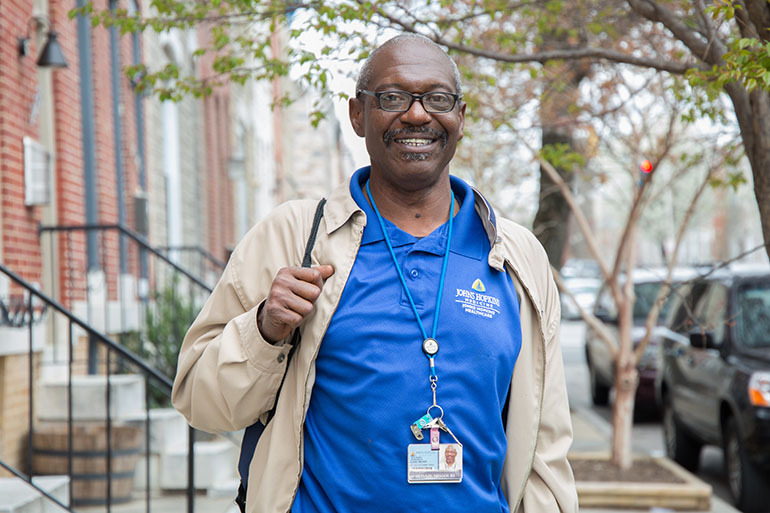

Donnie Missouri, 58, meets with 28-year-old Vincent Berry, one of the patients he regularly visits in his role as a community health worker at Johns Hopkins Hospital. (Francis Ying/KHN)

BALTIMORE — Donnie Missouri, 58, doesn’t have medical training. He started his health career in the linens department in Johns Hopkins Hospital. Now, he works on the front lines — one of the hospital’s non-medical workers who reaches out to patients who doctors think are at risk of suffering setbacks that will force them to return.

One recent day at the end of March, he visited Vincent Berry, a 28-year-old man who’s paralyzed from the waist down, a condition resulting from a years-ago gunshot wound after a drug deal went sour. Berry’s doing well medically, but he lives with his aging grandmother, in the upstairs bedroom of a narrow apartment where he relies on help from friends and family to be able to leave. Missouri has been trying to help him secure independent, wheelchair-accessible housing that will make it possible for him go to school or pursue other activities that might move his life forward.

Right now, “I can’t get out and go to school every day,” Berry said, adding that he just tries to make the best of everything. “I just — I know I want to be in a house. It doesn’t have to be the best house.”

Missouri’s goal is to connect people like Berry with resources like housing, transportation and other government benefits — factors that influence health but aren’t the doctor’s focus.

What’s Missouri’s secret? It’s a combination, he says, of building rapport, meeting patients at home and, most importantly, understanding the challenges — medical and not — his neighbors face. “You have to know your community,” he said of the East Baltimore neighborhood where he lives and works. “If you don’t … it ain’t going to work.”

Vincent Berry, 28, who was paralyzed from a gunshot wound several years ago, lives with his grandmother in East Baltimore. Donnie Missouri, 58, a Johns Hopkins Hospital aide, is trying to help him find him stable, wheelchair-accessible housing. (Francis Ying/KHN)

What Missouri does is hardly a novel concept. For decades, community health workers have tried to fill the system’s gaps. Often hired by the local health department, they take on diverse public health initiatives — running diabetes or nutrition education programs, counseling patients to stick to their medication regimens or teaching new mothers about vaccinations.

But now, hospitals across the country are turning to them in a bid to revamp patient care. They are using these aides to strengthen their relationships with patients and surrounding neighborhoods — improving the community’s health and, along the way, their own finances.

Part of it is spurred by the 2010 federal health reform, which introduced a number of changes in how Medicare pays hospitals.

Similar efforts are underway on the state level, through Medicaid payments and health insurance regulations. Health insurers, too, are starting to show interest in figuring out how they might pay for these services.

“We need to do things differently than what we had been before,” said Ken Fawcett, a physician and the vice president of the community health worker initiative at Spectrum Health in Grand Rapids, Michigan. “People are starting to recognize there are non-health care related variables that have a profound impact.”

Challenges persist, though, in figuring out how to finance community health worker programs and regulate the growing workforce.

How It’s Done

Preliminary research suggests health systems are seeing returns on these investments. Patients stay healthier. Fewer are readmitted. That reduces how much expensive, often-not-profitable care hospitals need to give, yielding a financial payoff.

“Because of this new policy environment, health care systems are going to be held accountable” for people’s health, said Shreya Kangovi, an assistant professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine, who directs its center for community health workers.

The American Hospital Association doesn’t systematically track how many health systems have launched community health worker programs. It’s becoming “much more common,” said Ken Anderson, chief operating officer of the hospital trade group’s Health Research and Education Trust. “This area of interest seems to be very much front and center for hospitals.”

Community health workers are often uniquely positioned to help their clients — the hospital patients.

Frequently, workers have had similar life experiences — maybe addiction, navigating the criminal justice system or simply facing difficulties gaining access to care or other neighborhood’s challenges — so they can connect with patients in ways doctors and nurses don’t, said Scott Berkowitz, Johns Hopkins’ senior medical director for accountable care.

For Missouri, that’s invaluable. When visiting patients, he avoids business clothes that might render him unapproachable, opting for a shirt and lanyard showing he’s from Hopkins, but also jeans and brown walking shoes. He jokes with Berry’s grandmother, and recognizes his dog. After fist-bumping Berry goodbye — they’ll check in later by phone, they confirm — he can cross the street to his next client, a woman with substance abuse problems. He’s a recovering addict himself.

After leaving the apartment of client Vincent Berry, Donnie Missouri, 58, a Johns Hopkins Hospital community health worker, will walk across the street to see his next client, who is dealing with a substance abuse issue. (Francis Ying/KHN)

How do programs work? Take the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School. Community health workers — who are full-time hospital employees — are assigned patients. They assess patients’ needs and develop relationships spanning months. An early study of the program found patients who participate are less likely to keep returning to the hospital and have better outcomes.

Penn is betting these efforts will ultimately mean savings, so it’s investing upfront: funding the program through its own operating expenses. Some health systems are using grants from private foundations or the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to get started. New York Presbyterian Hospital, affiliated with Columbia University, started its community health worker pilot a decade ago, using grant funding. Since then, program leaders have convinced the hospital not only to pay for the program but to expand it, citing healthier, more satisfied patients.

Hopkins got a federal grant from the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation to launch its program in 2012. The funding is ending this year, but it is planning to continue anyway.

In Maryland, the state has taken steps to reform hospital payments — rewarding health systems for keeping patients healthy enough that they don’t need hospital treatment. That adds financial incentives for Hopkins and other hospitals, encouraging them to use strategies such as outreach by community health workers.

Federal policies also add appeal. The University of Maryland Medical Center, in West Baltimore, for instance, started its community health worker project last year after it was penalized by Medicare for failing to meet national standards regarding how many patients it readmitted within 30 days of discharge.

The hospital’s seen readmissions drop by about half, said Zina Kendell, the program’s manager, but the program doesn’t save enough to offset the cost of running it. Still, the hospital is looking into expanding it, said Charles Callahan, vice president of population health. “We have a model we believe in,” Kendell said.

Meanwhile, state and federal regulators are grappling with how to set standards for community health workers’ training and certification.

The hospital’s seen readmissions drop by about half, said Zina Kendell, the program’s manager, but the program doesn’t save enough to offset the cost of running it. Still, the hospital is looking into expanding it, said Charles Callahan, vice president of population health. “We have a model we believe in,” Kendell said.

More than 20 states have instituted regulations or created oversight committees, according to Sharon Moffatt, interim executive director of the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials.

But there’s no consensus on the best level of scrutiny for community health workers.

Take background checks, an idea that “comes up all the time,” said Carl Rush, who heads the Project on Community Health Worker Policy & Practice at the Institute for Health Policy at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

Though well-intentioned, that standard can be counterproductive, he said. “There is a legitimate argument to be made that people who have exposure with the corrections system or criminal justice generally are better-equipped to work with people” coming through community programs.

Institutions like Penn and Hopkins train workers before sending them into the field. But Missouri, the Hopkins community health worker, said knowing the city, its resources and residents matters most.

“A lot of people sit in their office and talk about how they’re all about community,” he said. “[But] when’s the last time you got into it and found out how your community works?”

This article was reprinted from kaiserhealthnews.org with permission from the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Kaiser Health News, an editorially independent news service, is a program of the Kaiser Family Foundation, a nonpartisan health care policy research organization unaffiliated with Kaiser Permanente.