“African American men in particular are at an increased risk; they are 37 percent more likely to develop lung cancer than white men, even though their overall exposure to cigarette smoke – the primary risk factor for lung cancer – is lower.”

“African American men in particular are at an increased risk; they are 37 percent more likely to develop lung cancer than white men, even though their overall exposure to cigarette smoke – the primary risk factor for lung cancer – is lower.”

Lung cancer is raging in the black community and it is particularly a death sentence for African-American males. The American Lung Association recently released a new report Too Many Cases, Too Many Deaths: Lung Cancer in African Americans that paints a very grim picture of the toll the disease is taking on blacks in America. Lung cancer has been the leading cause of death among men since the 1950s and in 1987 it exceeded breast cancer as the leading cause of cancer deaths among women. It is now disproportionately impacting African-Americans.

The report notes that the prevalence of lung cancer among blacks is consistent with other health disparities in the nation. Data shows that the “African American population experiences higher rates of death from heart disease, cancer, cerebrovascular disease and HIV/AIDS than any other racial or ethnic group.” For all cancers, blacks are confronted with a death rate that is 25 percent higher than whites.

Lung cancer, a preventable illness, is devastating the black community. African-Americans have a higher death rate from lung cancer than any other racial or ethnic group in the United States. The occurrence of lung cancer hits black men particularly hard despite their having the same smoking rate as white men, and data that shows white men consume 30-40 percent more cigarettes than black men.

Researchers believe health disparities in lung cancer are driven by several realities, including biological, environmental, political and cultural factors. Among issues contributing to risk factors that result in health disparities, researchers have examined smoking behavior, workplace exposure, genetics, access to health care, discrimination and social stress, among a number of issues. The report examines six factors that have been shown to contribute to the lung cancer disparity. They are tobacco use, preventive behavior, socioeconomic status, environmental exposures and genetics.

Tobacco Use

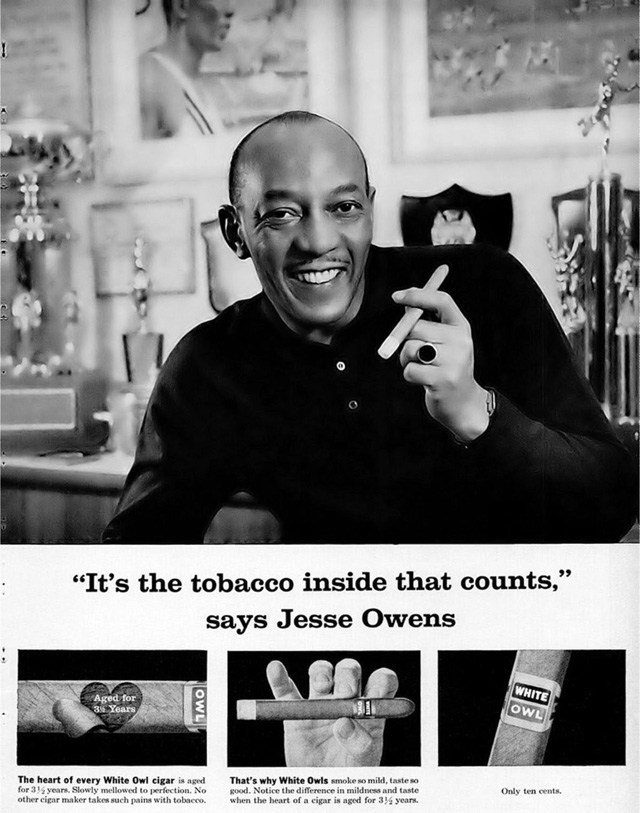

The African-American community was targeted by the tobacco industry through a marketing strategy the report points out researchers have identified as the “African Americanization of menthol cigarettes.” In 2002, a review of cigarette advertising found that magazines targeting blacks were “nearly 10 times more likely to have cigarette ads than more general audience magazines.” Meaning that publications blacks were more likely to read were plastered with advertisements from tobacco companies. It was a strategy that worked, as a 2009 report from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) showed 83 percent of African American smokers aged 12 and older chose menthol cigarettes, as compared to 32 percent of Hispanic smokers and 24 percent of white smokers. This has accelerated black deaths from lung cancer as menthol smokers have higher levels of cotinine in their blood, a byproduct of nicotine, a substance that researchers believe may be associated with more severe forms of addiction. Research also shows that smokers that prefer menthol cigarettes are less confident in their ability to quit smoking and less likely to attempt cessation.

The African-American community was targeted by the tobacco industry through a marketing strategy the report points out researchers have identified as the “African Americanization of menthol cigarettes.” In 2002, a review of cigarette advertising found that magazines targeting blacks were “nearly 10 times more likely to have cigarette ads than more general audience magazines.” Meaning that publications blacks were more likely to read were plastered with advertisements from tobacco companies. It was a strategy that worked, as a 2009 report from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) showed 83 percent of African American smokers aged 12 and older chose menthol cigarettes, as compared to 32 percent of Hispanic smokers and 24 percent of white smokers. This has accelerated black deaths from lung cancer as menthol smokers have higher levels of cotinine in their blood, a byproduct of nicotine, a substance that researchers believe may be associated with more severe forms of addiction. Research also shows that smokers that prefer menthol cigarettes are less confident in their ability to quit smoking and less likely to attempt cessation.

The tobacco industry was also adept at manipulating public opinion and building support for its products. The industry used Madison Avenue imagery to promote itself as good corporate citizens and enlisted celebrities in that effort. It also made strategic contributions to African-American cultural organizations to curry favor with Black leadership, and essentially wall off any possible criticism of the negative health effects of cigarettes.

Preventive Behavior

The research shows blacks hold beliefs that may interfere with their ability to quit smoking. Too Many Cases, Too Many Deaths cites a 2005 analysis that showed while all races largely underestimate the lethal nature of smoking, blacks “appear to be more confused about prevention recommendations, to doubt the association of cancer with smoking and lifestyle and to be reluctant to seek preventive care because of fear of the disease.”

The disbelief in the danger of smoking and lack of belief in what the data shows about the lethal nature of certain behaviors appears to be sending blacks to premature death.

Socioeconomic Factors

Socioeconomic factors include education, income and employment, and they all play a significant role in the health status of African-Americans in the United States. There are approximately 40 million people living in poverty in the United States, representing 13 percent of the population, but 24 percent of blacks are in poverty as compared to 8 percent of whites. While there are more whites who are poor in America, there is a higher incidence of poverty among African-Americans.

Poverty is known to exacerbate health disparities, and access to health insurance and health care, the quality of care available, health literacy and lifestyle are all contributing factors. It is clear that socioeconomic status tracks with cancer rates and the progression of the disease. The report indicates that for “lung, colorectal and prostate cancers combined, death rates among both African American and white men with 12 or fewer years of education are more than twice those of men with higher levels of education.” People of lower socio-economic status have poorer diets, engage in less physical activity that could lead to better health, and some engage in behaviors that increase cancer risks.

Environmental Factors

Where you live, or where you are able to live, can have a profound effect on your health. Race and income determine where people can live and often places blacks in areas where they are exposed to dangerous pollutants. The report references a review of recent research that shows black neighborhoods on average face 1.5 times higher levels of toxins in the air as other communities. It also notes that there is evidence that shows that the overall cancer risk for blacks increases the more segregated their community is from other communities. Given the highly segregated nature of housing in America, the risks posed to African-Americans’ health is significant.

African-Americans also have higher exposure to second-hand smoke than all other groups. Second-hand smoke is the cause of 3,400 lung cancer deaths annually in the United States. There is also the threat posed by exposure to radon in the home. Radon is the leading cause of lung cancer in non-smokers and the second leading cause of lung cancer overall. There has not been a direct link found between radon and cancer deaths by race or ethnicity. Still, the ability to make the necessary steps to fix issues in a home that might cause the release of radon or the lack of control over conditions in rental or public housing can make exposure to radon more prevalent for the poor and people of color.

Another environmental factor is occupation. Where African-Americans work can contribute to the incidence of lung cancer among blacks. Occupational exposure to smoke, dust and chemicals increase susceptibility to lung cancer. However, the report suggests that the role of the workplace in the disparity in lung cancer rates for blacks is not well defined. Still, it is well established that blacks are often employed in jobs that expose them to cancer causing agents. One such area is transportation; where exposure to diesel exhaust has been identified by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) as causing a 40 percent higher risk of lung cancer than for individuals who are not exposed.

Genetics

The impact of genetics on lung cancer rates is still an unknown and there are still more questions than answers at this point. Researchers have focused on two genes that appear to be linked to nicotine dependence and an increased risk of lung cancer. What is known is that African-Americans are less likely to have these genes than whites, but, the risk for lung cancer is greater for blacks than whites when that gene is present.

There has also been a focus on cotinine, a byproduct of nicotine that lingers in the bloodstream after smoking. It is known that African American smokers have higher levels of cotinine in their blood than whites, and this is believed to be due in some measure by racial differences in the way nicotine is metabolized in the body. The higher levels of cotinine in African-Americans might also be the result of higher exposure to nicotine and other carcinogens.

One of the issues affecting research on the possible role of genetics on lung cancer and the development of treatments has been the low participation rate of African-Americans in clinical trials. The historical experiences of blacks with the health care profession as well as other beliefs might be influencing their attitudes toward clinical trials.

Too Many Deaths

The evidence is clear that African-Americans as a group are not only more likely to get lung cancer than other groups, but are more likely to succumb to lung cancer. The average length of time an African-American survives after a diagnosis of lung cancer is lower than whites. Only 12 percent live longer than five years from the diagnosis as compared to 16 percent of whites. One of the underlying causes for this disparity is the difference in how black patients interact with health care providers. The report notes.

• African-Americans get diagnosed later when their cancer is more advanced

• African-Americans wait longer to receive treatment after they have been diagnosed

• African-Americans are more likely to refuse treatment

• African-Americans are more likely to die in the hospital after surgery

The report cites unequal access to health care, unequal quality of health care and racism and social stress as causes that increase the likelihood of blacks dying from lung cancer. Access to health care, or lack of access, is well established as a significant factor affecting the quality of life of African-Americans. Twenty-one percent of blacks are uninsured and some 38 percent of blacks report an unmet health need based upon an inability to visit a physician when needed because of the cost. Due to the lack of access to primary care, many African-Americans are more likely to receive treatment in an emergency room of a hospital. The inability to regularly see a physician hampers preventive care measures. The experience that blacks have had with discrimination has also caused them to delay in seeking medical care and treatment, and a mistrust in treatment recommendations. Health care providers have also engaged in discriminatory practices, such as limiting referrals of black patients to specialists for treatment, which then limits treatment options.

The report cites unequal access to health care, unequal quality of health care and racism and social stress as causes that increase the likelihood of blacks dying from lung cancer. Access to health care, or lack of access, is well established as a significant factor affecting the quality of life of African-Americans. Twenty-one percent of blacks are uninsured and some 38 percent of blacks report an unmet health need based upon an inability to visit a physician when needed because of the cost. Due to the lack of access to primary care, many African-Americans are more likely to receive treatment in an emergency room of a hospital. The inability to regularly see a physician hampers preventive care measures. The experience that blacks have had with discrimination has also caused them to delay in seeking medical care and treatment, and a mistrust in treatment recommendations. Health care providers have also engaged in discriminatory practices, such as limiting referrals of black patients to specialists for treatment, which then limits treatment options.

There are also differences in access to quality lung cancer care. African-Americans receive less quality care and do not get the same treatment for their condition as whites. Blacks are less likely to receive chemotherapy and less likely to undergo staging and even if staged, are less likely to have surgery. One of the major impediments for better health outcomes for blacks is the dearth of African-American physicians in the United States. Blacks are significantly underrepresented in the medical field, comprising just 4 percent of the physician workforce according to statistics compiled by the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). The provider-patient relationship is key for wellness and issues of cultural competence in health care continue to affect African-Americans who generally perceive white doctors to be less engaging, supportive and partnering in their health care.

As it does in all other areas of American life, race plays a role in the health status of African-Americans. Like genetics, the link between race and wellness is still far from clearly understood but given the racial disparities in health outcomes there is ample evidence to infer that racism and discrimination are at the root of the poor mental and physical health of African-Americans. Stress attributed to racism and being the victims of discrimination is thought by many health care providers to increase the risk of lung cancer and premature death from lung cancer for African-Americans.

What’s Next

Too Many Cases, Too Many Deaths suggests a number of steps to attack the high incidence of lung cancer and lung cancer deaths in the African-American community. Among the steps suggested, better data collection, systems-change strategies that involve changing workplace practices, educating employers on their power as healthcare purchasers, and the recruitment and training of health professionals. The report also recommends the replication of effective strategies and cites the efforts of several private and public organizations that are undertaking that work on a national, regional and local level.