For all of the shock over the police killing of 17 year-old Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, his death is part of a pattern in the narrative of the United States. Since the Republic’s founding in 1776 Black men, first Africans and then those born on this soil, have been cast as enemies of the state. Black men have been demonized since slavery, looked upon with suspicion by white society, and painted as less than human. The typecasting of Black men as less than has been sustained through the ages and is evident today in popular culture and perceived in the education arena and criminal justice system. Michael Brown is just the latest victim of police brutality albeit his death has become a flashpoint given its public nature in this age of social media.

It had only been weeks after the nation saw the shocking video of Eric Garner being put in a choke hold by a New York City police officer in Staten Island that Ferguson Missouri caught our attention. The New York Medical Examiner ruled Garner’s death a homicide caused by the application of a choke hold. His supposed offense was selling loose cigarettes on the street. Like Brown, it is the ease by which police officers inflict deadly force that remains shocking even against the backdrop of our nation’s racial history. Garner is seen on the video taking a non-confrontational posture as he is confronted by police, and he is heard telling the officer that he could not breathe as the choke hold is applied in front of several officers on the scene. According to eyewitness accounts in Ferguson, the same non-confrontational posture was taken by Michael Brown. Recently released autopsy results show that Officer Darren Wilson shot Brown six times, with two bullets hitting him in the head. The indifference to Brown’s life was evident by the manner in which the police allowed his body to lay in the street for almost five hours. As if by exclamation point, another unarmed Black man – Ezell Ford – was killed by police in Los Angeles just days after Brown was felled in Ferguson.

It had only been weeks after the nation saw the shocking video of Eric Garner being put in a choke hold by a New York City police officer in Staten Island that Ferguson Missouri caught our attention. The New York Medical Examiner ruled Garner’s death a homicide caused by the application of a choke hold. His supposed offense was selling loose cigarettes on the street. Like Brown, it is the ease by which police officers inflict deadly force that remains shocking even against the backdrop of our nation’s racial history. Garner is seen on the video taking a non-confrontational posture as he is confronted by police, and he is heard telling the officer that he could not breathe as the choke hold is applied in front of several officers on the scene. According to eyewitness accounts in Ferguson, the same non-confrontational posture was taken by Michael Brown. Recently released autopsy results show that Officer Darren Wilson shot Brown six times, with two bullets hitting him in the head. The indifference to Brown’s life was evident by the manner in which the police allowed his body to lay in the street for almost five hours. As if by exclamation point, another unarmed Black man – Ezell Ford – was killed by police in Los Angeles just days after Brown was felled in Ferguson.

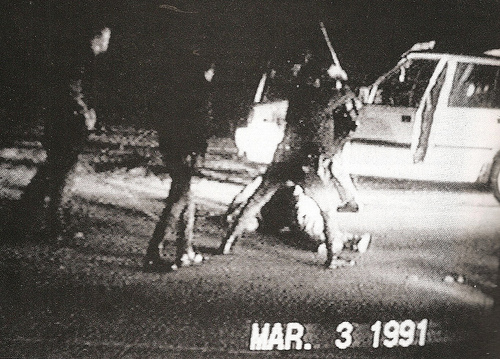

For all the characterizations of Black men as violent, incident after incident show in confrontations with police, Black males are often in retreat and assuming a positon of surrender. It is why protesters in Ferguson have adopted the ‘hands up, don’t shoot’ position as their rallying cry. The image of the cooperative Black male is counter to news and theatrical imagery of combative Black men, almost zombie like in their zest to take on the police. The circumstances surrounding the deaths of Brown and Garner recall the 1991 assault on Rodney King in Los Angeles County, an episode of police violence that was infamously captured on videotape. The fact that all three men were consciously attempting to show that they were not a threat to the officers involved sheds a light on a deep-seated bias that training alone will not resolve.

There is something deeply and disturbingly American about the killing of Michael Brown and other Black men by the police. Violence against Black men is ingrained in American culture. There is a historical ribbon that threads through the violence inflicted upon male Africans aboard slave vessels, in the plantation fields, the terrorism of lynchings and their subjugation during Jim Crow to the police brutality we have witnessed for decades. The real connection between historical episodes of violence against Black males and current events is the ease at which Black men are beaten and killed by individuals sworn to uphold the law. It is the leisurely torture and killing of Black men that hearkens back to an era when junk science robbed Black men of their humanity and reduced their value to that of a barnyard animal. The only difference is that the value of Black men as free or cheap labor once spared lives, with the exception of when the offense was supposedly violating a white female, but today the value of Black men has dropped to the point where their deaths seldom register on the nation’s consciousness.

Since surrender does not appear to be an option for Black men when confronted by police, it begs the question if law enforcement has now determined that the killing of Black men carries no criminal or social penalty? In these cases the same scenario generally plays out. The offending officer is put on desk duty or suspended with pay. The local police union voices its support of the officer, as was the case of Officer Daniel Pantaleo who applied the choke hold to Eric Garner, the media refuses to probe the underlying issues of the local police department, and the victim’s reputation is tarnished by inferences that he has a criminal record or was found possessing a weapon.

The character assassination of the victim begins almost instantly in most cases. In 1990 in the suburban community of Teaneck New Jersey a 15 year old Black youth, Phillip Pannell, was shot and killed by a white police officer. Autopsy results showed that Pannell was shot in the back, with his arms raised in surrender as he was cornered in a backyard with no escape route. Almost immediately the Teaneck police bludgeoned Pannell’s reputation, casting him as a thug and claiming he had a firearm and was a threat to the officer. The major daily newspaper also initially contributed to the imagery of a young thug when it ran a mug shot of Phillip from a juvenile, non-violent offense on its front page. The paper, The Record, stopped using the photo after editors met with community leaders who voiced concern over what was perceived to be bias in its reporting.

The Black bogeyman is part of American culture. He takes the form of the sex starved deviant on the prowl for white women, the superhuman and mindless Mandingo who intimidates with his sexual prowess and raw athleticism, or the genetically violent criminal who must be contained at any and all costs. These stereotypes seem extreme but they result in the early suspension and expulsion of Black boys from school, the tilt of the criminal justice system against Black males and the determination that Black boys can only excel on the athletic field. What rational minded individuals would dismiss as irrational characterizations, American society promotes such imagery and then embeds it in public policy. It results in police not seeing humans when they encounter Black men but some deviant mutant lacking a conscious and a soul. It makes the use of force against Black men less resistant to better judgment and the killing of them easier to justify.

Ferguson is not an anomaly. It is who we are as a country. It reflects on our low regard for Black men and the nation’s high tolerance for their deaths. Absent significant reforms in policing in local departments and higher penalties for the unwarranted use of deadly force, the culture of policing lends itself to recurring episodes of brutality. The virus of police brutality cannot be trained away, it will take systemic reform of law enforcement, from recruiting to training and the imposition of career ending penalties for officers engaged in violating the rights of Black men. Police in Ferguson, New York City, Los Angeles and other communities did not develop their appetite for brutality against Black men overnight; it is genetically embedded in the culture of policing in America.