Washington continues in its stalemate, with a hidebound Republican establishment clinging in death throws to some ancient regime of plutocratic rule. The nation is left without vision for a way out of the current economic malaise that, if unchecked, will deepen inequality and cement the fate of the “middle class state.”

This week marks 49 years since President Lyndon B. Johnson delivered the commencement address at Howard University. Looking at his words also shows us what vision others had and how our compromises have us stumbling instead of leaping forward. We can’t move forward if our language does not force results. In an era of rising inequality, settling for “equality of opportunity” is not a vision for moving forward. Here is what Johnson said on June 4, 1965:

"…the task is to give 20 million Negroes the same chance as every other American to learn and grow, to work and share in society, to develop their abilities—… to pursue their individual happiness.

To this end equal opportunity is essential, but not enough, not enough. Men and women of all races are born with the same range of abilities. But ability is not just the product of birth. Ability is stretched or stunted by the family that you live with, and the neighborhood you live in—by the school you go to and the poverty or the richness of your surroundings. It is the product of a hundred unseen forces playing upon the little infant, the child and finally the man."

Johnson was clear, adding emphasis, “[E]qual opportunity is essential, but not enough, not enough.” Inequalities feed on themselves; equal opportunity is only one means to achieve equality. And, as Johnson probably understood, claims of “equal opportunity” become a way to blame the victim when outcomes are not equal; it allows policies to fall short since they aim low—not at achieving equal outcomes.

Seventy years ago this week, Allied units stormed the beaches of Normandy. June 6, 1944, marked the beginning of the end for the reign of Nazi terror in Europe. My uncle, Nero Henderson, did not land on that day, but the 4083rd Quartermaster Service assigned to the 1st Engineering Special Brigade followed immediately to establish the beachhead, clear mines and barriers so the necessary logistical support could fuel the Allies’ run to Paris and on. Unfortunately, my uncle died near Utah Beach on July 12, 1944.

He was born into a segregated world; Princess Anne County (now the city of Virginia Beach) did not have education for blacks beyond the eighth grade. My grandparents moved to give their children a chance to attend Booker T. Washington High School in Norfolk. My uncle is buried in Calvary Cemetery, set aside by Norfolk in 1877 for the burial of African Americans, segregated in death.

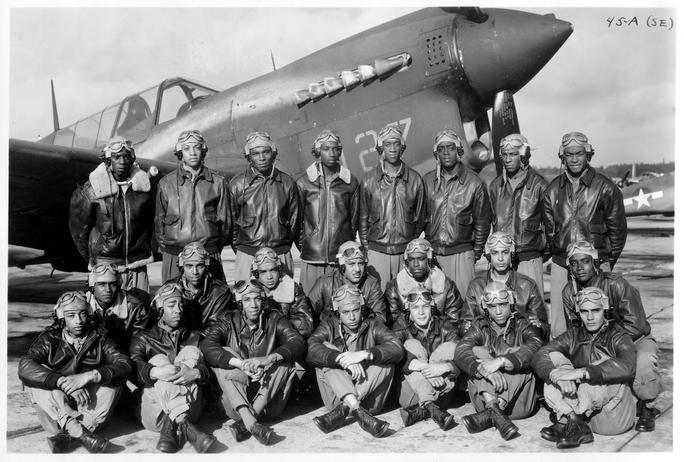

My parents were World War II veterans: my mother served in the Women’s Army Corps, and my dad was one of the Tuskegee Airmen. When they settled in Norfolk after the war, they had limited opportunities to take advantage of any GI Bill provisions. My father attended Virginia State University (in Norfolk then Petersburg)—Virginia’s only public college admitting African Americans. In a city riddled with race restrictive covenants, housing opportunities were limited for African Americans—even World War II veterans. It would be 10 years later before my father could use his GI benefit to buy a home in Washington, D.C.

Eventually, my father earned a doctorate in physics and taught at Howard; which put me in the yard that June to hear Johnson’s speech. As Father’s Day nears, I marvel at my father’s accomplishment overcoming layers of inequality. But having heroes is not a plan.

Google recently released its EEO-1 data, showing its shocking lack of diversity. They took to the normal excuse that qualified African Americans are scarce (like a black Ph.D. in Physics?); a sad excuse for a company that specializes in searching data. The District–Maryland–Virginia area is home to an information technology industry as large as Silicon Valley’s; except its computer workforce is 22% black. Among U.S. citizens, in 2012, the National Science Foundation reports 10.6% of people earning bachelor's degrees in computer science were African Americans. Google’s report shows 2% of its workforce is black.

America’s current challenge of inequality is bigger than race. If we cannot move to results-oriented policy on race, how will we tackle broad issues of class inequality? First, we must drop “equal opportunity” and move to equal outcomes; not excuses.

Dr. William Spriggs is the chief economist for the AFL-CIO.